Got and opportunity to talk about the active projects that we’re currently working on.

The magazine was published since 10 Sep 2017.

Thanks to Andrew Biggs and BangkokPost for having us a change to speak and support us as always.

– – –

“Manit Intaraphim is relentless in his crusade to get access and justice for disabled people”

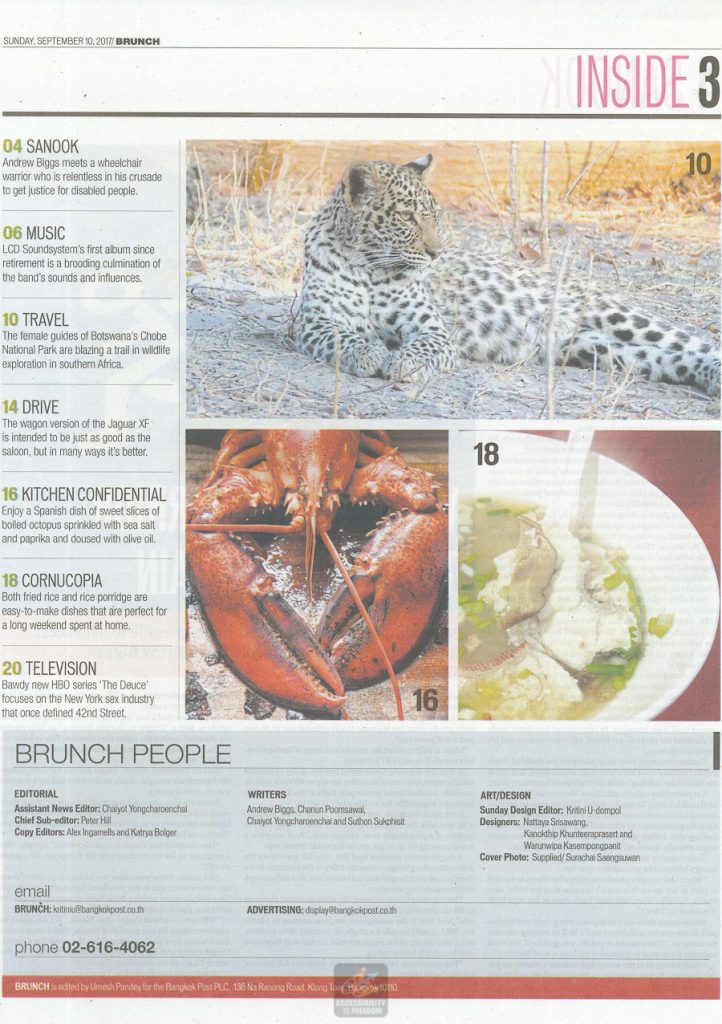

Andrew Biggs meets a wheelchair warrior who is relentless in his crusade to get justice for disabled people.

Two major events shaped the life of Manit Intaraphim. One was falling asleep at the wheel. The other was a bad bowl of corn soup. The first occurred early one Monday morning more than two decades ago as he was riding his big bike to work. The ensuing crash broke his spine and put him in hospital for 12 months. He was a paraplegic at the age of 24.

The second incident happened three years ago. Having a late dinner at the restaurant in Foodland Srinakarin supermarket, he ordered a bowl of soup. The soup came with cheese on toast, which, when microwaved, rendered the cheese cardboard and the toast inedible. He’d told them before not to microwave the toast; they did it again. He demanded to see the Foodland manager, who ended up on the receiving end of a fiery tirade about the perils of bad microwaving. “And another thing,” he said at the end, “By law you’re supposed to have parking spaces for the disabled.”

From that moment on, Manit become a man in a wheelchair on a mission. And in three short years he has become Thailand’s wheelchair warrior — an unrelenting, unapologetic champion of disabled rights in two categories, namely, car parks and his nemesis, the BTS.

You may have seen Manit on page one of the just two weeks ago as part of a consumer rights’ network called Transportation For All being vocal in its opposition to the BTS announcement of skytrain fare hikes. Seated among other advocates at the press conference, he looked quite reserved in his conservative dark suit.

It was all an act. It was in stark contrast to his usual media persona, that of a slightly crazed crusader going by the nickname Saba (“named after the fish”). He makes videos and live streams calling for justice for the disabled and posts them on his website, accessibilityisfreedom.org.

Manit’s a good-looking man originally from Udon Thani who, when not bugging organisations over their lack of access, can be found exercising in Bangkok’s Rama IX Park, trying to best his time for 10km in a wheelchair. He is the face of wheelchair justice in car parks. His videos often entail driving to supermarket car parks then filming ablebodied people who park in disabled spots, interviewing those offenders on the spot in often embarrassing conversations.

He bullies supermarkets and malls into following the law on car parks for the disabled. Central, Foodland, Fortune, MBK, Megabangna … he has a story about them all, but says they usually end happily. “Sometimes I have to threaten to sue before they take action,” he says. “But they have all complied. Except for MBK. They promised to lift their game, but they haven’t.”

It all started with a video clip he made at Central Pattaya not long after the corn soup incident. His clip went viral, thanks to some English subtitles, and he appeared on many TV shows.

To the department store’s credit, Central quickly started provided proper spaces for the disabled, and their policy has spread to all their branches. In fact you can just about credit all disabled car parks to our friend, his video camera and his legion of followers.

Thailand has strict laws about access for the disabled. Every public building must have access for wheelchairs, and not at the back of the building beside the tradesman’s entrance either.

Car parks have equally strict laws. There must be one disabled park for every 50 regular parks. They must be larger than normal to accommodate a car and a wheelchair side by side. Security guards must be educated on proper procedure when dealing with selfish able-bodied drivers (though one could argue attitude-disabled) who blithely park in the spots.

Unfortunately in Thailand, seniority and the persona of being a phuyai take precedence over law.

“When I ask security guards why they allow the able-bodied to park in our spots, they say it’s because they are VIPs,” says Manit. “I reply: ‘Then why don’t you change the sign from ‘Disabled’ to ‘VIPs’?” Manit claims there are two reasons why people continue to park in his spaces: selfishness and a lack of any punishment for doing so. “If you smoke in public, you get fined. But what happens if you park in a disabled parking space? Nothing.”

Which brings us to the wheelchair warrior’s current target: the skytrain. It, too, appears to be unfazed by any threat of punishment.

Manit’s hands start to clench and his face slightly reddens when he talks about the BTS and its owner, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration.

“They want to increase the fares,” he says. “We say — not until you do what the Supreme Court ordered you to do two and a half years ago.”

Manit is talking about the contentious issue of having elevators installed in all 23 BTS stations.

Before the Supreme Court order, just five of the 23 stations had elevators, with one of those five having an elevator on only one side. Another had a power pole right at the lift entrance, making it impossible for a wheelchair to get in.

Even more bizarrely, one station, Chong Nonsi, featured a lift that took the disabled right down smack bang into the middle of a perpetually busy intersection. “And not even a zebra crossing for us to get across the road,” Manit says.

A single station requires four lifts. One lift goes up to the ticket office. Another goes from the office to the platform. Since there is both an inbound and outbound line, that means each station needs four elevators.

The Supreme Court ordered the BMA to install elevators in all stations within one year. They didn’t say “four elevators”. And that is the outrageous catch; according to Manit, the BMA craftily installed a single lift in many of its stations, as in, one-fourth of the required total. In that way they were able to comply by the ruling.

“Two years later, 18 stations are still without a full elevator system,” says Manit.

Manit claims there is no penalty for the BMA not following the court order. And so, he must employ the same tactics he used back on that night when his corn soup was no good. He’s going to kick up a stink.

He has launched a new campaign in which he says Bangkok needs to find a “Knight In Shining Armour” to help enable the disabled receive the rights they deserve. This is a play on words. The Bangkok governor’s name is Asawin, which means “knight” in Thai.

And on Thursday, Sept 21, Manit and his network of disabled friends are going to march on the BMA and lay a funereal wreath at its doorstep.

Manit’s brazen approach has made inroads in the last three years, but it also uses up a lot of resources. He divides his time between his career as an IT consultant and wheelchair warrior. The former funds the latter.

“The disabled don’t want to make enemies,” he says. “But sometimes in life it’s necessary to stir things up. We cannot sit still.”

And finally, three years after the bad soup incident, there has been movement in the Foodland Srinakarin parking lot. Two new disabled parking areas have sprung up right at the entrance, guarded by security guards.

“We have to praise them,” says Manit. “If I am going to condemn them for not providing access, then I must praise them when they make changes. It’s the same for Central, Megabangna and Big C. They have made changes for the better. That’s all we are asking of society.”

He still visits Foodland often.

Does he still order corn soup? He smiles.

“They’ve learned how to make it properly now,” he says.

“Thanks to me.”

10 Sep 2017 By Andrew Biggs/Brunch Magazine/SANOOK/BangkokPost

—

/Saba

AccessibilityIsFreedom

Accessibility Is Freedom เข้าถึงและเท่าเทียม | Accessible and Equal

Accessibility Is Freedom เข้าถึงและเท่าเทียม | Accessible and Equal